ai transcription of this post for the hearing imparied

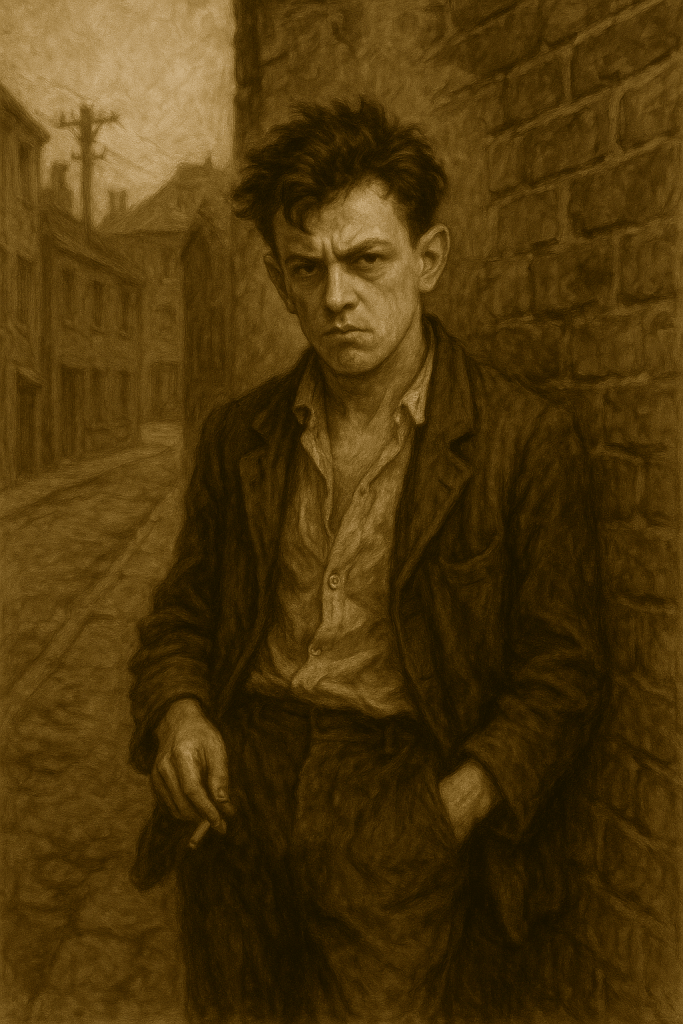

In the somber remnants of 19th-century England, before he became the infamous occultist who would declare himself the Great Beast, Aleister Crowley was simply Edward Alexander, an only child born into a rigid religious sect that called itself the Plymouth Brethren. What seems, on the surface, a footnote in his biography is, in truth, the crucible that forged his rebellion. Crowley’s defiance wasn’t born in a vacuum. It was a direct, fiery response to the suffocating morality and enforced spiritual purity of his upbringing. And to understand the cult he later created, one must first understand the cult he was born into.

The Roots of the Brethren

The Plymouth Brethren began not in Plymouth, but in Dublin, Ireland, around 1825. A small group of Evangelical Christians, Edward Cronin, John Nelson Darby, Anthony Norris Groves, and J.G. Bellett, grew disillusioned with the structure and perceived corruption of the Anglican Church. They envisioned a return to “New Testament Christianity”, a church without hierarchy, clergy, or ornamentation, where Scripture ruled unchallenged and believers met in simple fellowship. Their philosophy: total separation from “the world.”

By the early 1830s, Darby carried this vision to Plymouth, England, where the movement would find its namesake. What began as a radical rejection of religious formalism soon hardened into a rigid orthodoxy of its own. As the sect grew, it fractured. In 1848, a theological dispute between Darby and fellow leader Benjamin Wills Newton exploded into a schism that birthed two major branches: the Open Brethren, who maintained some flexibility and fellowship with outsiders, and the Exclusive Brethren, who walled themselves off with absolute doctrinal control. Crowley’s family belonged to the latter.

By the late 19th century, the Exclusive Brethren, had expanded out across the globe from Britain to Europe, Australia to North America, pulling tight communities into even tighter theological knots. Rules weren’t just doctrine; they were lifestyle. Members were discouraged from associating with outsiders, marrying beyond the group, or questioning authority. The Bible was the final word. Joy was muted. Doubt was dangerous.

Edward Alexander Crowley was born in 1875 into a family drenched in the Exclusive Brethren’s dogma. His father, Edward Crowley Sr., was a devout follower and a traveling preacher for the sect. The elder Crowley viewed the world as fallen, and his son as a soul to be shielded. Religion wasn’t a tradition in the household; it was law, obsession, and burden.

Crowley’s mother, more emotionally distant and severe, would reportedly refer to her son as “the Beast” when he misbehaved, an insult that young Aleister would later wear as a crown.

His childhood was carved out of sermons, psalms, and the constant fear of divine punishment. There were no birthday parties, no fairy tales, no secular books. Playfulness was vanity. Self-expression was sin.

This ironclad religious upbringing was both formative and damaging. Crowley grew up isolated, yet observant. His sharp intellect and emerging libido chafed against the limits imposed by his family’s faith.

Young Aleister was a curious, spirited, and willful child. He asked questions, challenged rules, and expressed defiance toward the strict religious discipline imposed on him. To his mother, steeped in a literalist reading of the Bible, this behavior wasn’t merely unruly, it was evil. In her worldview, his rebelliousness aligned him with the “Beast” of Revelation, the apocalyptic figure associated with Satan. The term wasn’t just an insult. It was a theological indictment.

When his father died in 1887, the thirteen-year-old Crowley experienced not just grief, but a spiritual rupture. The man who embodied the certainty of God’s plan was gone, and in his place remained silence… and questions.

It didn’t take long for the questions to turn to rebellion.

As a teenager, Crowley began what he would later describe as his deliberate campaign to be “bad for Satan.” He smoked. He drank. He sought out prostitutes. He wrote poetry dripping with blasphemy and sexual liberation. He read books his mother would have burned. This wasn’t ordinary teenage angst but an exorcism of everything the Plymouth Brethren had placed inside him.

At Cambridge, he traded in Edward for Aleister, a name that sounded less English and more mythical, something befitting a man attempting to rewrite his origin. He immersed himself in esotericism, alchemy, Kabbalah, and Eastern mysticism. Eventually, he would find his way to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and begin laying the groundwork for what would become Thelema, his own magickal religion.

But at the root of Thelema was always the shadow of the Brethren. “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law” was, in part, a retort to the suffocating control of his childhood.

If the Brethren taught obedience and submission to God, Crowley preached individual sovereignty and communion with one’s True Will. If they taught salvation through restraint, he offered liberation through indulgence. His rituals were lush, sensual, filled with symbols and secrets, the very things denied to him as a child.

Criticism of the Plymouth Brethren has followed the group for over a century. Charles Spurgeon condemned its theological rigidity as early as 1869. Other Christian thinkers accused Darby and his followers of promoting spiritual elitism and heresy. As time wore on, deeper wounds emerged.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, splinter groups, especially the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, have faced mounting accusations of abuse, financial control, excommunication, and the destruction of families through shunning. A 1974 murder-suicide in England by member Roger Panes, believed to be influenced by church discipline, cast a dark pall over the Brethren’s image.

Former members now describe the sect as a high-control environment, a closed system of psychological pressure dressed in biblical clothing. Emotional suppression. Social isolation. Obedience over inquiry.

These were the very elements Crowley fled from. In fleeing, He didn’t just reject the Brethren; he became their mirror image. Where they demanded silence, he thundered. Where they demanded purity, he reveled in taboo. Where they erased the self, he exalted it.

Aleister Crowley is often remembered for the blasphemy, the magic, the scandal. But beneath the flamboyance lies the quieter truth: he was a boy once, kneeling in a pew, taught to fear his own thoughts. He was forged in a religion that prized erasure of self as sanctity. And in breaking free, he didn’t just defy that structure… he built his own.

To understand Crowley’s drive, one must understand the Plymouth Brethren’s grip. The irony is as poetic as it is tragic: in trying to raise a son of God, the Brethren helped awaken the self-declared Beast.

And in doing so, they birthed one of the most enigmatic, and polarizing, spiritual figures of modern history.

Aleister Crowley did not reject God in silence. He did so with the thunder of a prophet tearing down the temple he was raised in. His words, laced with intellect and venom, leave no doubt about how deeply he despised the Christianity of his youth, particularly the brand embodied by the Plymouth Brethren.

In his semi-autobiographical Confessions, Crowley reflects on the spiritual severance required for magical work, citing even Jesus’s disowning of his mother and brethren as justification.

“In every Magical, or similar system,” he wrote, “it is invariably the first condition which the Aspirant must fulfill: he must once and for all and for ever put his family outside his magical circle.”

The spiritual path, in Crowley’s eyes, demanded nothing less than a brutal disconnection from the very people who had first indoctrinated him: his family, devout Exclusive Brethren.

He didn’t simply turn away from Christianity; he dismantled it in his writing.

In “Magick: Liber ABA”, he quipped, “One would go mad if one took the Bible seriously; but to take it seriously one must be already mad.”

The statement is more than a jab. It is a diagnostic diagnosis of the psychological strain he believed religious literalism inflicted. Having grown up immersed in daily scripture, surrounded by a culture that taught absolute obedience to biblical text, Crowley saw the Brethren’s reverence not as piety but as pathology.

Crowley’s disdain went deeper than theology into the personal.

“I did not hate God or Christ,” he wrote later, “but merely the God and Christ of the people whom I hated.”

He drew a careful line between the spiritual figures themselves and the distorted, punishing caricatures wielded by institutions like the Brethren. For Crowley, Christ might have been a mystic. The God of his childhood, however, was a tyrant disguised in holiness.

One of the most telling glimpses into Crowley’s inner battle comes from a journal entry where he recounts a harrowing spiritual crisis: “I was in the death struggle with self: God and Satan fought for my soul those three long hours. God conquered, now I have only one doubt left. Which of the twain was God?”

This was an existential upheaval. Crowley wasn’t just choosing freedom over faith; he was trying to determine which voice in his soul was truth and which was indoctrination.

Later, as he founded Thelema, Crowley declared openly that spiritual power had nothing to do with obedience or moral code.

“I was anxious to prove that spiritual progress did not depend on religious or moral codes… Magick would yield its secrets to the infidel and the libertine.”

This was an exorcism of his former life, the doctrine of restraint replaced with the ecstasy of individual will.

Even as he mocked and rewrote Christianity, he often used its own scriptures to justify his break from it. The very Book that had been used to restrict him became, in his hands, a tool of liberation. In this reversal lies the most potent irony of all: Crowley’s rejection of the Plymouth Brethren was not a clean escape, but a lifelong battle. Their presence haunted him, shaping the very rebellion that would define him. In building his own religion, Crowley did not just break with the past, but he built a temple from its shattered stones.

Thelema, at its core, is often seen as a stark departure from Christianity, but in truth, it is a mirror turned sideways, reflecting the darker threads of the very religion it sought to transcend. Crowley, raised under the unyielding weight of the Plymouth Brethren, did not simply abandon Christian theology; he reworked it, infused it with his own shadows, and twisted its moral absolutes into metaphysical questions. In his religion, sin is not transgression but repression. Judgment is not divine but internal.

Crowley took the Christian obsession with sacrifice, suffering, and redemption and inverted it, offering instead the ecstasy of the will, the sanctity of indulgence, and the holiness of the self. Rituals within Thelema often mimic the cadence and solemnity of Christian ceremony, yet they are laced with eroticism, taboo, and infinite defiance.

The Beast, a symbol of evil in Revelations, became Crowley’s own title and an embodiment not of malevolence, but of liberated power. Even his Gnostic Mass, with its altar, wine, and consecration, drips with the Christian Eucharist, but in Thelema, it celebrates the union of opposites, the divine in flesh, and the sovereignty of will over submission.

In this way, Thelema is not just a new religion but more so, Christianity’s shadow, gathered into ritual, reframed through rebellion, and transformed into something radically individual. Crowley did not discard the symbols of his upbringing; he devoured them, reassembled them, and lit them aflame in the name of freedom.

Aleister Crowley is often remembered as a provocateur, an occultist, even a monster, but beneath the theatrics and the darkness he wrapped himself in was a deeply fractured child. Born into a doctrine that demanded obedience over curiosity, suppression over expression, and shame over individuality, Crowley grew up under the constant gaze of judgment.

The Exclusive Plymouth Brethren, with their rigid moralism and apocalyptic fear, offered no space for the tender chaos of childhood. There was no room for wonder, or questioning, or self-discovery. Only the harsh binary of saved or damned. In such an environment, a child learns not to listen inwardly but to fear the very nature of their own thoughts.

Psychologically, this kind of indoctrination fragments the developing self. Crowley’s later life was marked by brilliance, addiction, obsession, and constant reinvention… and reads like the odyssey of a man exiled from himself, trying to reconstruct an identity out of ashes. His rebellion was loud and deliberate, but behind it was a desperate hunger to reclaim autonomy. He didn’t just reject God; he needed to build a world where he could exist without annihilation.

The sensuality, the ritual, the grandeur of Thelema weren’t only spiritual innovations. They were coping mechanisms. Crowley’s magick was, in many ways, therapy in ritual form, a place where he could finally speak without being condemned.

Aleister Crowley fathered at least five children over the course of his turbulent life. But his role as a father was distant, erratic, and often emotionally cold. His daughter Lola Zaza, born from his marriage to Rose Kelly, had minimal contact with him throughout her life. When they reunited briefly during her teenage years, Crowley recorded the encounter in his diary with cruel judgment, writing that Lola was unmanageable, and labeling her stupid, plain, and ill-tempered. The bitterness of that entry reveals a total absence of paternal warmth or understanding.

Lola, in turn, rejected her father’s legacy entirely. She chose a quiet, private life as a nursery governess, intentionally distancing herself from the scandal and spectacle that trailed Crowley’s name. She made no public statements defending or claiming his spiritual lineage, nor did she embrace his teachings. Her silence was its own form of renunciation.

Another daughter, Astarte Lulu Panthea, was born in 1920 from Crowley’s relationship with Ninette Shumway. Like Lola, she remained distant from her father’s world. Astarte lived in Oakland, California, and passed away in 2014. Very little is known about her views on Crowley, but her total absence from Thelemic communities and literature suggests a life deliberately lived apart from his mythos. She, too, seemed to walk quietly in the opposite direction.

Across the lives of his children, a consistent pattern emerges: they did not inherit his philosophy, nor did they appear to desire the mantle of his spiritual identity. His personal writings are filled with irritation and rejection, not affection. Their life choices reflect a conscious disengagement from the chaos and controversy of their father’s world. If Crowley believed his legacy would be carried through blood, that belief died quietly with their decision to live in anonymity. In their silence, there is no voice of devotion, only the sound of doors quietly closing behind them.

Aleister Crowley stands as a haunting testament to how biblical religion can shatter a child’s soul before it ever learns its own name, leaving a broken man to emerge, lost in the maze of his own delusions and fractured identity.

When we view Aleister Crowley through this lens, we see not a villain, but a case study in how deeply religious trauma can wound a child. He is what happens when spiritual systems prize control over compassion, and when dogma suffocates the soul before it has a chance to bloom.

His life invites us to ask hard questions: not just about him, but about the quiet, invisible damage still done today to children raised in systems that teach them to fear their own humanity.

Crowley’s story is not a justification, but a warning. And for those willing to look beyond the myth, it is also a plea for gentler ways to raise the next generation of seekers, with the freedom to explore without indoctrination.

Let them grow up safe and free.

Discover more from Vennie Kocsis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.